Last September, we gave our readers a definitive introduction to the city’s latest urban core, which was then just beginning its skyward ascent. Over the past year, we released dozens of updates regarding the myriad of projects coming to Long Island City, particularly those rising along the streets of the Court Square district. Today YIMBY revisits the growing community and looks at the progress that has been made over the past year. We also look at the 11,000+ residential units, over a million square feet of office space, and around 1,800 hotel rooms that are under construction or proposed for the neighborhood.

Long Island City, united under the 11101 zip code, sits at the westernmost point of Queens, across the river from Midtown Manhattan. Similar in size to Lower Manhattan, Long Island City is also effectively a peninsula, confined not only by water to the west and south, but also by the two-mile-long Sunnyside Railyard to the southwest.

Looking northwest from the intersection of Thomson and Skillman avenues. The railyard starts on the other side of the fence.

The commercial-industrial enclave of Blissville, which sits on the other side of the railyard, is also technically a part of LIC, but thanks to the railyard, it feels more like the periphery of Sunnyside.

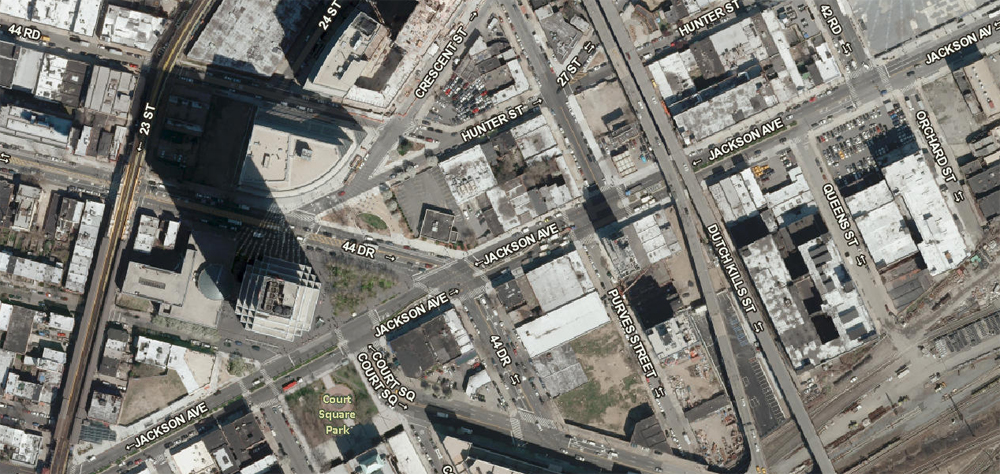

The neighborhood’s focal point lies within the Court Square district, which is approximately bounded by 41st Avenue to the north, 11th Avenue to the west, and the railyard to the south and east. The Queensboro Bridge touches down upon Queens Plaza in its northern section, which continues 1,000 feet east to Dutch Kills Green, the gateway into the borough and one of its most important junctions.

Dutch Kills Green at the junction of Queens Plaza, Northern Boulevard, Queens Boulevard, and Jackson Avenue. Looking northeast.

From this point, the nearly 200-foot-wide Queens Boulevard runs southeast for seven-and-a-half miles as one of the borough’s key arterials. Northern Boulevard, which branches off to the northeast, anchors the northern portions of both Queens and Nassau counties, and continues along the northern shore of Long Island as New York State Route 25A. The one-mile-long Jackson Avenue, which runs southwest from this intersection, extends Northern Boulevard, anchors much of Long Island City, and connects to the Queens-Midtown Tunnel, the Long Island Expressway, and the Brooklyn-bound Pulaski Bridge. In addition, every subway line that connects Queens to Manhattan (E, F, M, N, Q, R, 7), the Brooklyn-bound G train, and the Long Island Rail Road all pass through, or near, this crucial junction.

The Past

Despite its pivotal location and one-stop proximity to Midtown, the Court Square skyline has always been surprisingly bare. Its streets were dominated by rowhomes and factory buildings since the late 19th century.

The Queens Plaza/Court Square neighborhood in June 16, 1936. Looking southeast from the Queensboro Bridge across Vernon Boulevard. Credit: Percy Loomis Sperr. New York Public Library. Image ID 727285F

While the old factory lofts appear imposing at the ground level, they barely register on the skyline, which, for much of its existence, was pierced only by chimney stacks, occasional church spires (such as that of the Church of St. Mary on Vernon Boulevard), and the 12-story, neo-Gothic office building topped by a clock tower at 29-27 Queens Plaza North. The clock tower reigned as the borough’s tallest from 1927 to 1990. That year it was surpassed by the 658-foot-tall Citibank Building, now known as One Court Square, which snatched the title of the city’s tallest building outside of Manhattan from Brooklyn’s Williamsburg Savings Bank, built in 1925. The octagonal pillar faces the Court Square Park and the 1874 Long Island City Courthouse, which gave the neighborhood its name. But for much of the following twenty years, the rest of the neighborhood continued to exist as scattered rowhomes, warehouses, auto shops, and parking lots, made particularly desolate and dreary by the crime and poverty that blossomed since the 1970’s.

Long Island City skyline in the foreground. October 2003. Left to right: One Court Square, Citylights, Avalon Riverview, and the former Hunters Point Power Plant.

The resurgence of Long Island City began along its East River waterfront. The 42-story Citylights apartment building, erected in 1997, was joined by a phalanx of similarly-sized residential towers, such as the East Coast LIC complex built by TF Cornerstone, over the course of the following decade. Though the riverfront continues its growth along Hunters Point South, the development spotlight has shifted further inland to Court Square, encouraged by a then-recent neighborhood upzoning.

Left: Midtown Manhattan, with the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge passing over Roosevelt Island. Center: Hunters Point. Right: Court Square.

The curvy glass facades of the 16-story Court Square Place and 15-story Court Square Two, built just north of One Court Square in 2006 and 2007 respectively, rejuvenated the local office market.

Court Square Place, with Linc LIC on the left and One and Two Court Square on the right. Looking southeast.

In 2011, the sweeping blue glass curve of Two Gotham Center at Queens Plaza rose 22 stories, or 315 feet tall, about half as high as the reigning title-holder.

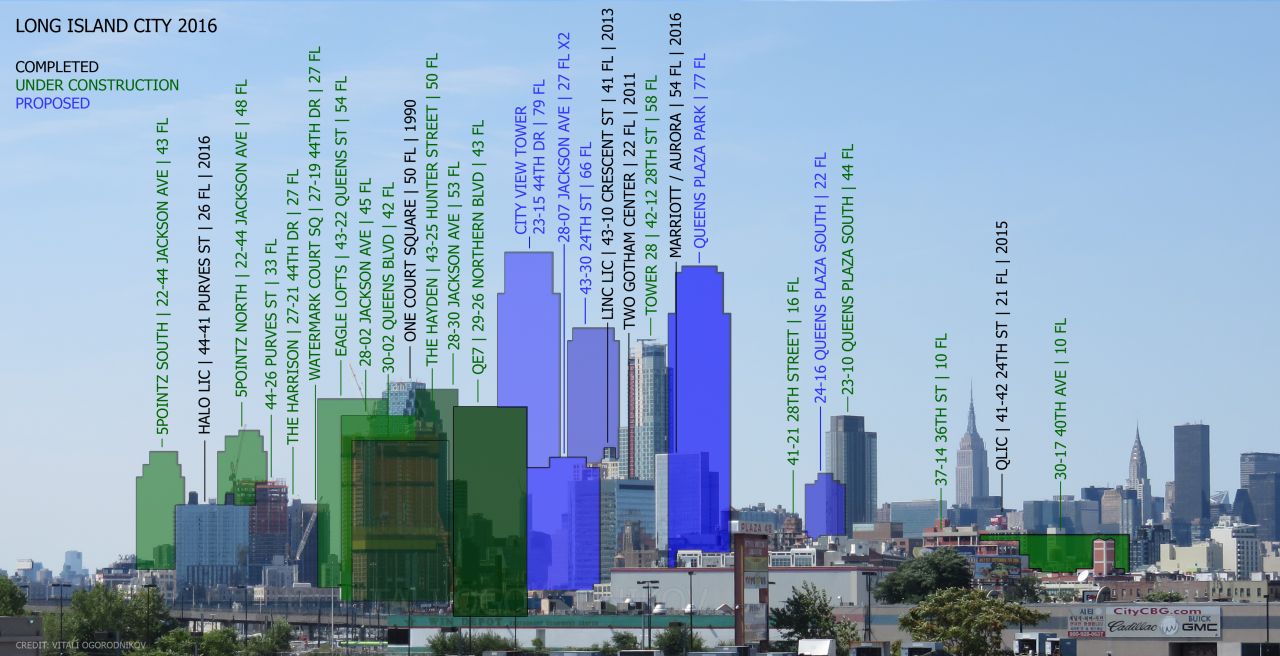

The neighborhood’s first residential high-rises started rising north of Queens Plaza and along Purves Street. 27 on 27th, a slender, 27-story Heatherwood Properties tower arrived just south of Queens Plaza in 2013. True skyline change came the same year with the completion of the 41-story, 429-foot-tall Linc LIC at 43-10 Crescent Street. The 709-unit tower, developed by Rockrose, became the borough’s second-tallest building and its tallest residential structure, retaining both titles by the point when we reviewed the local skyline last September.

At that time, three more prominent buildings joined the skyline: the 26-story, 284-unit, glass-and-brick slab of the Halo LIC at 44-41 Purves Street; the 21-story, 421-unit QLIC at 41-42 24th Street; and the dramatic, 31-story, angled slab of 29-11 Queens Plaza North, which would combine the 160-room Marriott Courtyard Long Island City hotel on the lower floors with the 135-unit Aurora apartment complex above. All three have been completed since then: QLIC around December 2015, Halo LIC in April 2016, and 29-11 Queens Plaza North in May (hotel) and July (residences). In addition, during this period we witnessed the completion of the 11-story, 184-unit sculptural stack of residences at 22-22 Jackson Avenue; 11-story, 124-unit office-to-residential conversion at Luna LIC at 42-15 Crescent Street; and the nine-story, 48-unit Baker House at 41-07 Crescent Street. The nine-story, 37-unit Factory House at 42-60 Crescent Street is also effectively complete, with tenants expected to start moving in any day. In combination, these projects introduce 1,109 apartments and 160 hotel rooms to the neighborhood.

The Present

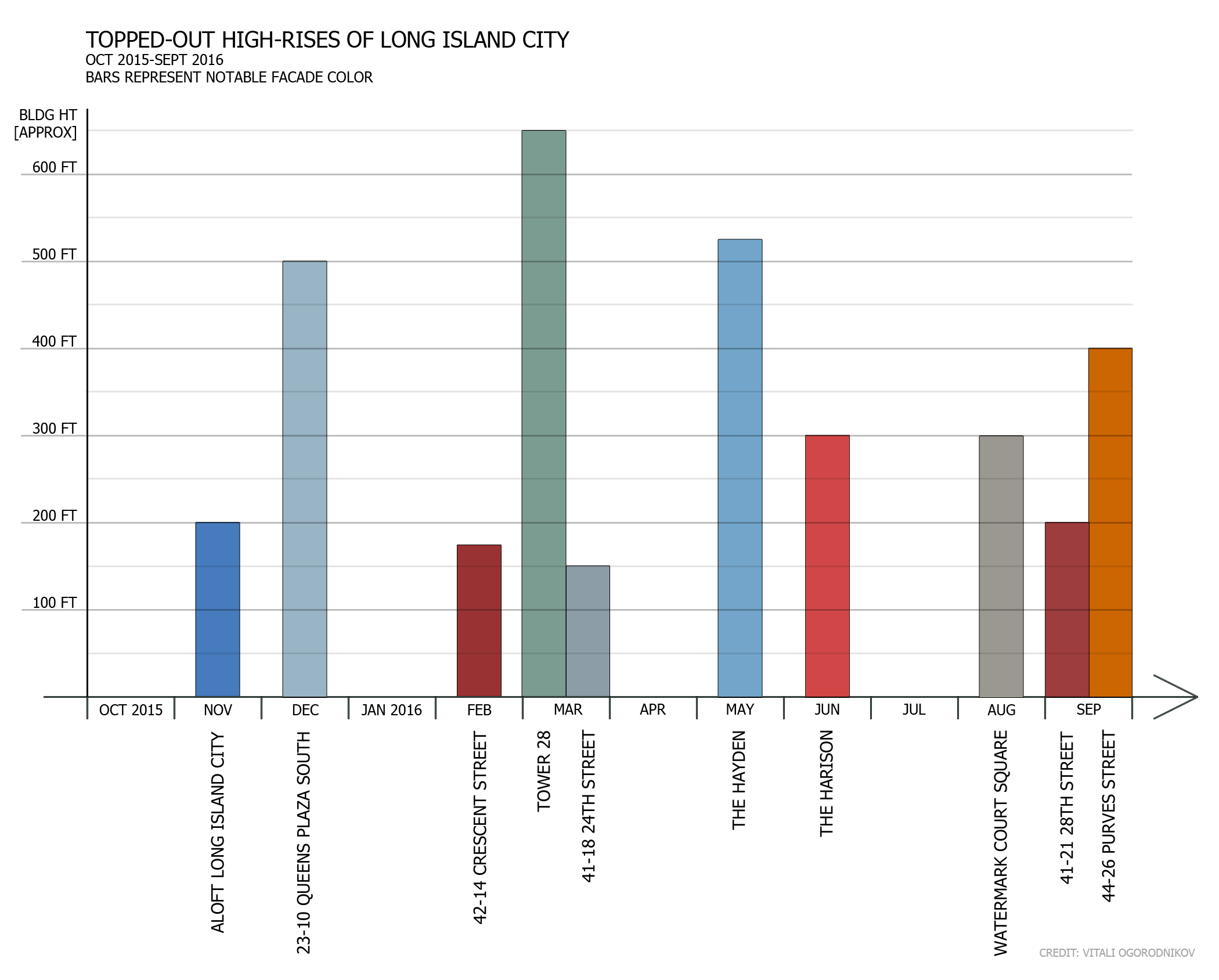

In the year that has passed since then, the Court Square skyline has more than doubled in size. The singular dominance of One Court Square has been usurped by the 58-story Tower 28 near Queens Plaza. At 647 feet tall, it stands just a few feet shorter than the reigning champion. The new skyline revolves around these two focal points, with most new tall buildings clustered around the two. When counting topped-out and nearly topped-out buildings over the past year, the LIC skyline added four projects within the 500-foot height range, as well as six more measuring around 300 feet and above, forming a sizable plateau.

Here is a rundown of every building 12 stories or above that has been topped-out over the past year.

Tower 28. 42-12 28th Street. 58 floors. Residential [477 units], retail – Heatherwood Properties [developer] – Goldstein, Hill & West [architect] – topped-out: March 2016. Upon completion, Tower 28 would become the city’s tallest residential building outside Manhattan, and the tallest apartment tower between Manhattan and Boston. Its slender profile is the first to truly challenge the dominance of One Court Square.

Looking southeast, with the Queensboro Bridge viaduct on the foreground. Tower 28 is in the center. September 2016.

Hayden – 43-25 Hunter Street – 50 floors – residential [974 units], retail – Rockrose Development [developer] – SLCE [architect] – topped-out: May 2016. Anchoring the massive structure that occupies almost an entire city block, the slanted slab of Hayden works in tandem with the adjacent One Court Square. From afar, Hayden serves as a complimentary pinnacle to the larger office building.

From up close, the two read as equals, as their diagonally-oriented, sheer glass facades dominate Jackson Avenue.

23-10 Queens Plaza South – 44 floors – residential [391 units], office – Property Markets Group [developer] – SLCE [architect] – topped-out: December 2015. 23-10 Queens Plaza South currently stands as the borough’s fourth-tallest building, and dominates its surroundings thanks to its position at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge, somewhat west of the main skyscraper cluster. The rectangular glass slab is joined to a renovated loft building that would be used for offices and parking. The tower’s prominent position allows for some of the most dramatic Manhattan views of any of its Court Square peers.

44-26 Purves Street – 33 floors – residential [270 units], retail – Brause Realty, the Gotham Organization [developers] – FXFOWLE [architect] – topped-out: September 2016. 44-26 Purves rises as a series of slender, staggered slabs. The striking horizontals of its glass facade, which would be enclosed within copper bands, would make it one of the most sophisticated buildings on the local skyline.

The Harrison – 27-21 44th Drive – 27 floors – residential [115 units], retail – Silvercup Properties [developer] – GF55 Partners [architect] – topped-out: June 2016. The rusticated brick facade, punctuated with deep windows set within stone trim, distinguish the Harrison as the neighborhood’s tallest traditionally-inspired building.

Watermark Court Square – 27-19 44th Drive – 27 floors – residential [168 units], retail – Twining Properties [developer] – Handel Architects [architect] – topped-out: August 2016. Watermark Court Square fuses tradition and modernity through its subtly-setbacked tower slab, clad in large, square windows set within a minimalist grid of gray brick.

Under-construction buildings, from left to right: Hayden (behind One Court Square), Aloft Hotel (background, center left), 28-10 Jackson Avenue, Watermark Court Square, The Harrison, and 44-26 Purves Street. The recently-completed Halo LIC is on the right.

Aloft Long Island City – 27-45 Jackson Avenue – 18 floors – hotel [176 rooms] – Nassim Seliktar [property owner] – Gene Kaufman [architect] – topped-out: November 2015. The bright blue facade pattern of the soon-to-be-tallest all-hotel building in Queens adds whimsy to the local skyline. Its asymetrical setbacks appear to be a take on the dynamic Art Deco spires across the river.

41-21 28th Street – 16 floors – residential [188 units] – All Year Management [developer] – Karl Fischer [architect] – topped-out: September 2016. This recently-topped-out, traditionally-inspired building sits within the neighborhood’s small district of pre-war commercial high-rises, located north of Queens Plaza. Its red-brick facade would be notable for its large, loft-like windows, which pay homage to the neighborhood’s industrial past.

41-18 24th Street – 13 floors – residential [87 units] – Lions Group [developer] – MY Architect [architect] – topped-out: March 2016. The light-colored, airy slab stands at the northwest corner of the neighborhood. Its presence contributes significantly to the block-long residential canyon that sprung up over the course of the past few years.

42-14 Crescent Street – 13 floors – residential [48 units], retail – Meadow Partners [developer] – John Fotiadis [architect] – topped-out: February 2016. The architect of 42-14 Crescent Street re-imagined the neighborhood’s industrial legacy in a distinctly vertical manner. Its bulk is visually broken down into two distinct masses, accented with dark steel trim.

42-14 Crescent Street is in the center. Eight more recently-completed, under-construction, and proposed projects are visible in the photo.

Rear elevation of 42-14 Crescent Street, with 44-26 Purves Street under construction in the background

Though buildings below the 12-story threshold do not register on the skyline, the recently-topped-out mid-rises scattered across the neighborhood deserve a mention. They serve the important function of integrating new skyscrapers with the pre-existing low-rises, while adding residences and retail in place of warehouses and dirt lots. This roster includes the 11-story, 55-unit building at 11-51 47th Avenue; the 10-story, 79-unit apartment building at 41-29 24th Street, just north of Queens Plaza; the nine-story, 86-unit Dutch LIC at 25-19 43rd Avenue (approaching topping-out); the nine-story, 32-unit Queens Boro Tower at 41-04 27th Street; the nine-story, 32-unit 42-50 27th Street; the nine-story, 108-room Hyatt Place Hotel at 27-07 43rd Avenue; and the eight-story, 36-unit residential at 24-12 42nd Road.

Each of the seventeen structures listed above topped out over the past year, translating into the average of 1.42 per month, or 0.83 if including only high-rises 12 stories and above. These buildings add up to 2,678 residential units and 284 hotel rooms, which are all expected to be completed shortly.

The block bounded by Purves and Thomson streets, Jackson Avenue and 44th Drive currently looks like a Fourth of July parade, with three American flags, which signify topping out, waving side-by-side from the adjacent pinnacles of 44-26 Purves, The Harrison, and Watermark Court Square.

Watermark Court Square (left) and the Harrison (right), with 44-26 Purves Street behind. Each building is marked by a topping-out flag.

The Future

By the time the topped-out developments open their doors, the attention of development watchers will be fixed upon the next crop of projects, currently in various stages of construction. 48- and 43-story towers will rise from the former site of the 5Pointz graffiti center at 22-44 Jackson Avenue. The pair, developed by G&M Realty and designed by HTO Architect, will feature 1,115 residential units. The three-tower complex at 28-10 Jackson Avenue, developed by Tishman Speyer and designed by Goldstein, Hill & West, will bring 1,771 residential units to the crossing of Jackson Avenue, Northern and Queens boulevards, and Queens Plaza.

The complex rises across the street from the 44-story, 415-unit QE7 at 29-26 Northern Boulevard, developed by Simon Baron Development and designed by Stephen B. Jacobs Group. A couple of blocks south, Rockrose is erecting their third major project in the neighborhood, at 43-22 Queens Street. The 54-story, 790-unit tower rises from the renovated lofts at the former Eagle Electric Factory. Other under-construction projects in the vicinity include the eight-story, 12-unit 42-44 Crescent Street; the 18-story, 195-unit 41-20 27th Street; the 20-story, 110-unit 42-10 27th Street; the eight-story, 15-unit 42-83 Hunter Street; the 25-story, 184-unit 27-17 42nd Road; the six-story, eight-unit 42-43 27th Street; the 15-story, 46-unit Steel Haus at 41-32 27th Street; the nine-story, 29-unit 41-21 23rd Street, the the six-story, 37-unit 23-01 41st Avenue; and the six-story, 44-unit 27-05 41st Avenue. The 4,763 residential units projected for the developments listed above would be supplemented by a number of smaller apartment buildings currently in progress along adjacent blocks.

Finally, a handful of projects are still in the proposal stages, some of which are currently undergoing site prep. Three of these would finally snatch the height crown away from One Court Square. The 79-story, 774-unit City View Tower, at 23-15 44th Drive, would rise around 1,000 feet tall, becoming the borough’s first supertall. The 921-foot tall, 77-story Queens Plaza Park at 29-27 41st Avenue is scheduled to rise behind the landmark clock tower, which was a local skyline fixture since 1927 (although the project may see a change of ownership, and likely change of design, in the near future). A 66-story, 709-unit apartment building is also planned at 43-30 24th Street, one block north of the City View Tower.

The current scope of proposals covers a variery of scales and uses. While around dozen hotels are planned or under construction in northern Long Island City, two proposals lie south of 41st Avenue. Tokyo Inn Co. has recently unveiled their plans for a 50-story, 1,260-room hotel at 24-09 Jackson Avenue, next to the Court Square subway station. 243 rooms are planned within a 17-story building that would rise at 41-08 Crescent Street at the corner of 41st Avenue, sharing space with 96 residences. New office space is on the drawing boards, as well. Tishman Speyer is proposing two 27-story office towers at 28-07 Jackson Avenue, which would clock in at 1.1 million square feet. The Vorea Group has recently filed for a 12-story, 65,000-square-foot commercial building at 23-20 Jackson Avenue. A 10-Story, 315,626-square-foot office structure is proposed by Alma Realty at 30-20 Northern Boulevard. As expected, residential proposals dominate the roster, with about a dozen projects planned to rise in the vicinity.

If everything pans out as planned, all of the under-construction and projects listed above would add over 11,000 apartments, well over a million square feet of office space, and 1,787 hotel rooms to the neighborhood. Amazingly, virtually every project mentioned in this feature above fits within an area that measures only around 110 acres, or 0.17 square miles, which is largely confined within the elevated curve of the 7 train and the blocks along Queens Plaza North.

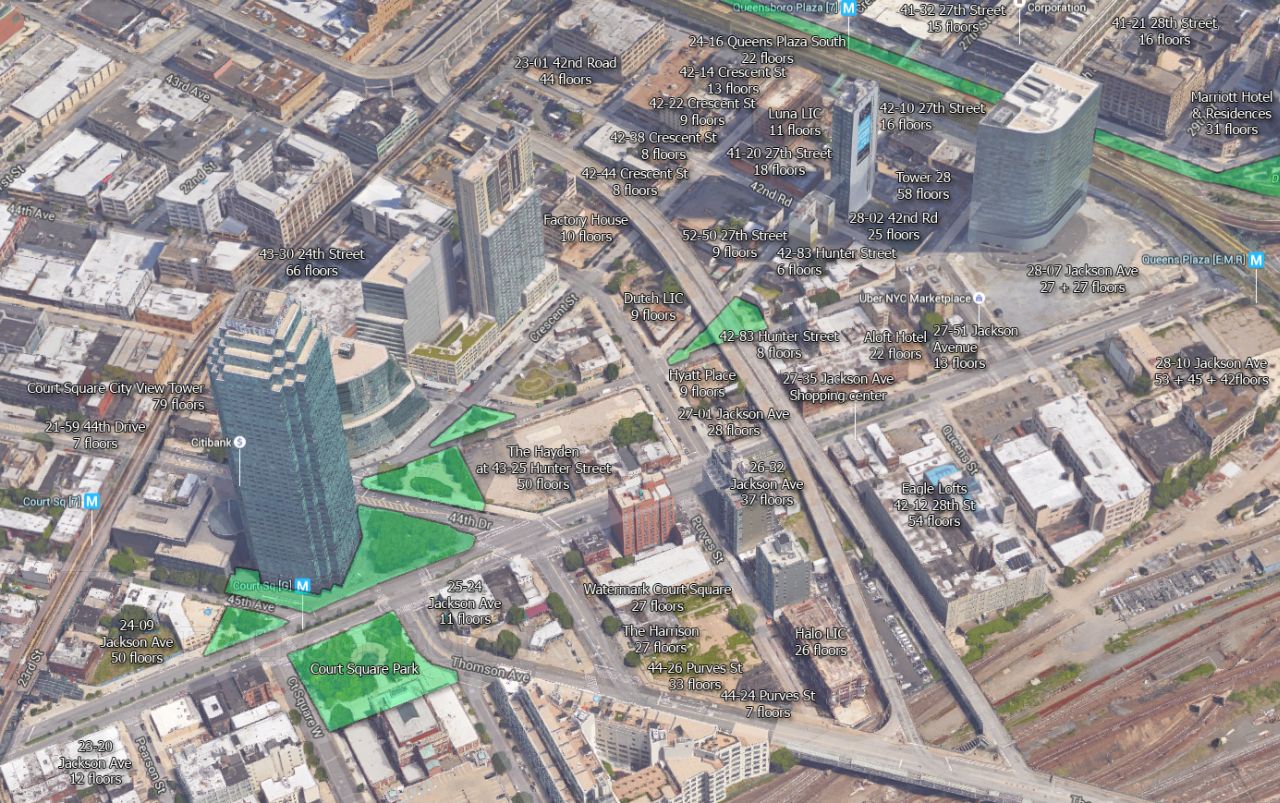

Ongoing projects in the neighborhood, with existing green space highlighted in green. Image underlay by Google, dating around 2014.

Understandably, there are those that are alarmed by the breathtaking amount of ongoing new development. In general, we applaud the initiative of citizens that are concerned with the well-being of their neighborhood. But while some concerns that we have heard revolve around real issues, others appear to come from an anti-development mindset that is averse to change of any kind. In the spirit of constructive dialogue, the following write-up will not address complaints that we find nonsensical, instead focusing on areas of improvement that are less subject to dispute. Although it is impossible to satisfy every developer, resident, and concerned citizen all at the same time, we can all agree that we wish to see responsible growth of the type that improves the area, generates income for developers and the community alike, and creates a vibrant, urban neighborhood that maximizes its potential without stretching it to the breaking point.

For the most part, we see the ongoing development as a net positive. If anything, the transformation of this former no-mans-land into a round-the-clock, urban community, a true epicenter for the borough, is way overdue. High density is most appropriate within areas that are best-served by both public transit and highway access. In these terms, Court Square is as good as it gets, as it is serviced by the E, M, R, N, Q, F, G, and 7 trains, the Long Island Rail Road that would soon connect directly to the Grand Central Terminal, a multitude of buses that travel to all parts of Queens a variety of subway lines, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, three of the most important boulevards in all of western Queens, the Queensboro Bridge, and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel. These options put Midtown Manhattan, the world’s largest office district, within a five-minute-long commute. This adjacency translates not only into convenient connection to Manhattan, but also for white-collar workers from all parts of Queens and Brooklyn that would prefer to avoid Manhattan during the office hours.

When it comes to developing high density, there is simply no better location anywhere in Queens, and arguably anywhere in the city outside of Manhattan. Still, mass transit improvements ought to be made, especially since many of the Brooklyn commuters re-routed by the impending L train shutdown would be re-routed through Court Square. Generally-expected suggestions include asking the MTA, a state-run agency, to run trains more frequently and to finally extend the length of the rolling stock along the G line to its full length. However, solutions are also possible at the local level. If the BQX, the Brooklyn-Queens streetcar connector, is built as proposed, it would run along 11th Street at Court Square’s western edge, further relieving incoming transit congestion. We would also urge Tishman Speyer to introduce a connection between the adjacent Queens Plaza and Queensboro Plaza stations when they would build their office complex at 28-07 Jackson Avenue, which would be located directly between the two. We also support more novel ideas for increasing local connectivity, such as the conceptual proposal to extend the Roosevelt Island Tram to Queens Plaza. Those that see this idea as a folly should consider the relief upon the local subway system, as many local Court Square commuters just might prefer the aerial connection to Midtown over the increasingly-crowded subway lines.

High-rise developments in Court Square are confined almost entirely within the 7 train loop, and along Queens Plaza and Jackson Avenue. Building scale drops off sharply beyond these boundaries, and new projects that rise outside this zone are fewer and further in between. Otherwise, new development barely impinges upon the traditional, low-rise, residential communities around the compact skyscraper district. The Hunters Point Historic District, with its tree-lined rowhome block, sits directly west of One Court Square, the tallest building in the borough. For the most part, new projects replace underused commercial sites, warehouses, and parking lots, which are inappropriate for such an important, accessible district. Still, whenever possible, we would strongly encourage developers to preserve architecturally valuable structures, or incorporate them into new projects. We applaud Rockrose Development, the Property Markets Group, and Greystone Development for following this path in their projects at 43-22 Queens Street, 23-10 Queens Plaza South, and 24-16 Queens Plaza South, respectively. We also understand the concern with the pending destruction of the attractive, historic Elks Lodge at at 21-42 44th Drive, which has garnered considerable community support in favor of its preservation. We understand both the developer’s desire to create new housing, as well as community outrage regarding the pending demolition. Still, we are sure that a compromise may be reached. If full preservation is impossible, we urge the developer to incorporates the existing facade into their new structure. Such preservation would add historical value to their new property while respecting local architectural legacy. The added expense of facade preservation is bound to pay for itself via the added distinction and property value to the finished product.

While the local roads can handle the influx of residents, it is more difficult to say the same in regards to the pedestrians. Since the district was built as a commercial and warehouse community, it was hardly built for walking across. At the moment, the city is planning to invest $38.5 million dollars into infrastructure improvement to make the neighborhood more pedestrian-friendly. Still, there is space for improvement even considering what is already proposed. Aside from Court Square Park, which was once half the size of its already tiny, current iteration, virtually all public space in the Court Square District core comes in the form of small public plazas.

Most of these were created over the decades as the city would close off redundant road segments formed by the neighborhood’s angular, irregular street grid.

Some of these plazas are pleasant in their own right, but their effect is diminished as they are separated by a series of roadways. Now that the neighborhood is changing again, there are new opportunities to consolidate some of the existing parklets into more continuous, and thus useful, green spaces. We would like to remind our readers of our suggestions that we already presented within a couple of articles, where we call for converting a stretch of Hunter Street that recent development made redundant in terms of traffic access.

Another opportunity is presented at the underutilized, city-owned space that sits beneath and next to the seven-block-long Queensboro Bridge Viaduct. As a major developer that is bringing thousands of units within three projects situated along the Viaduct, Rockrose is understandably interested in improving the locale. In 2013-2014, Rockrose, with the help of landscape architect Mathews Nielsen, developed a series of conceptual studies, seeking to transform the uninviting and cluttered spaces into a string of shaded, cozy public plazas.

Another consequence of the district’s industrial legacy is the lack of public destinations, both public and private. Such points of interest would make living in the neighborhood more convenient and, for lack of a better term, fun to be at. On one hand, positive change is on the way. The near-absence of supermarkets, restaurants, and retail would be alleviated by the new buildings in progress around the neighborhood, since the majority of them includes a commercial component on the ground floor. The Food Cellar occupies the ground floor of the Linc LIC apartment complex. Another supermarket would soon open at the base of the recently-completed Baker House, with more on their way. The conversion of the four-story office building at 27-35 Jackson Avenue would bring close to 50,000 square feet of shopping and dining to the center of the district. In terms of public institutions, the Steven Holl-designed Hunters Point Library, under construction at the Hunters Point waterfront several blocks west of Court Square, would become an instant icon, while relieving potential pressure upon the existing Court Square Library. The area is also home to MoMA PS1 and the Sculpture Center.

Still, we wish for more public amenities such as, whether in the form of theaters, movie halls, dining and nightlife destinations, or anything else that would bring joy to locals and visitors alike. For instance, the recently opened, cavernous halls with climbing walls at Brooklyn Boulders on 23-10 41st Avenue, is a step in the right direction. But we would welcome the addition of even basic staples of thriving neighborhoods, such as pharmacies and convenience stores, which are severely lacking at the moment.

Last but not least, the lack of schools is a critical issue for the neighborhood. With two schools projected for Hunters Point South and a third still under consideration, Court Square is flat out unprepared for the expected influx of school-aged children that would come with the new developments. We strongly urge city planners and developers alike to address this important issue as soon as possible, lest the incoming families find themselves and their children facing a crisis.

One of our recommended ways to get involved in the dialogue between city planners, developers, and the community would be to attend the meetings of the Court Square Civic Association. The inaugural meeting was held on September 29th at 7PM at MoMA PS1, where Amadeo Plaza, the Association President, joined a panel discussion by Jimmy Van Bramer, the City Council Majority Leader, and Paul Januszewski, the Rockrose Vice President of Planning. Many of the issues discussed above were addressed at the panel, which was later open to audience input.

Even those that hold no stake in the workings of the neighborhood would appreciate the growing profile of Long Island City. In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby, Jay Gatsby and Nick Carraway traverse the Queensboro Bridge on their way to Manhattan. “The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge,” Nick says, “is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world.”

Nearly a century later, the epic, mythical skyline of Midtown Manhattan is still second to none. Today, the once-underwhelming profile of Long Island City on the other end of the bridge has its own urban marvel to offer, as its green-and-blue glass towers rise like the Emerald City of Oz. The growing skyline is a beacon that speaks of the untapped potential of Queens for businesses, investors, and those that seek to set up a home either within Court Square or anywhere else in the city’s largest borough.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Thanks for a very long describing, now I’m busy and I will turn back to read this story soon.

Complete. (^_^)

Typo. Second paragraph. 21st Street to the west. Not 21st Ave

Thanks Theresa. Fixed.

This is truly amazing! I grew up in Long Island city. I’ve seen it in the 70’s, so to see it now and what it will become is truly breathtaking. Thanks for the article!

Great article.

Very informative article, well-balanced and comprehensive. The last paragraph with its Scott Fitzgerald quotation was an especially nice touch, gave me a full-body tingle with goosebumps. Thanks!

excellent article!

Thanks for the article. It was so informative of the new city being built. I attended Laquardia Community college. Im glad for all the improvements.

are these 20/80? how does someone with low income apply to get buy an apartment in any of these buildings?

Great article. The L-closing crisis can be ameliorated and Long Island City made even more Manhattan accessible by running the G train into Manhattan via the 60th Street BMT tunnel. This would require minimal new construction since the “11th Street Connector” currently used by the R train, already connects the Queens Plaza local tracks to the 60th Street tunnel. It is a few yards away from the G tunnel, which runs under Jackson Avenue. If the N is substituted for the R on the Queens Blvd line and brought into Manhattan through the 63rd St tunnel (now only half-utilized by F trains); and if the R substitutes for the N on the Astoria line, the 11th Street connector would be freed-up to accommodate G trains. Since the 60th St tunnel currently accommodates N,R and Q trains, it will be able to accommodate R, W and G trains when the Q moves from Astoria to the 2nd Avenue line at the end of 2016.

Great comprehensive article on the development history of LIC’s Court Square district and predictions for its future. However there are some glaring omissions when it comes to sound city planning. The height, bulk, density hyperbole neglects 3 major issues that threaten the livability of the district and could have serious ramifications in marketing the area compared to other NYC neighborhoods:

1. Lack of public open space. Through-out recorded history it is the availability of open space that measures the quality of democracy and progress of civilization via the events that take place in them. Two NYC examples would be Foley Square and Union Square. The under construction 11,000 new residential units, 1800 hotel rooms and over 1M square feet of commercial space combined with planned future projects and what’s already here all within less than a fifth of a square mile will grace the district with the worst open space ratio (open space to resident) in the City. This gross inadequacy will guarantee high turn-over. Adding one block of Hunter Street is grossly inadequate.

2. Lack of usable public transportation. Yes, most (not all) Queens subways stop in the district, but before they get to LIC stations during rush hour, they are already at or over capacity. This situation at the Number 7 Vernon/Jackson station is so dire that you have to que up just to get down the stairs and prepare to let several trains go by before there is room. Relying on a painfully slow moving trolley ½ mile away will not suffice.

3. Lack of foresight. The equivalent of this amount of development proposed in climate change savvy places such as northern Europe, China, and even the Middle East would feature buildings that decarbonize energy use, contain place destinations such as water parks, provide photovoltaic panels, skywalks, etc. This lack of 21st c. planning will make the district obsolete by 2030.

For future assessments how about less erection competition stats with other boroughs and more quality of life matters – especially those that address 21st c. issues.

WOW very interesting..amazing but scary that all those high rises with very little outdoor space.

I will never get the excitement for the Brooklyn Queens streetcar. Instead of extending the G a few miles, DeBlasio wants a streetcar that will zero compatibility with existing infrastructure. Cuomo and deblasio need to give their inane turf wars a rest already.

Streetcars SHOULD be added to the existing transit network but the route for the BQX is kinda dumb. Mixing circumferential and radial segments on a route is a recipe for lowered ridership. I feel very strongly that the Brooklyn Bridge SHOULD have streetcars running across it. Then you can run a streetcar from redhook to downtown manhattan, a one seat trip.

The three places I think need a streetcar/lightrail the most in the city are:

Fordham Road in the Bronx (running from COOP City to Inwood)

Main Street Flushing (from Flushing to Jamaica)

First Avenue in Manhattan (From Webster Ave in the Bronx, down 1st ave in manhattan, ave c, and then Broadway).

I would run center lane streetcars as they usually have a higher average speed.

odd silence that all these structure [except for the hotels] are 421-a tax exempt for 35 years; developers make millions of dollars and have no requirement to provide space for schools or libraries. it’s not sustainable: an area of many thousands of residents living in tax exempt structures that fail to meet the current building code for energy sustainability. i hope renters and other residents are aware of this and don’t expect services from the city that already lacks adequate funds to maintain parks.

the parks [sic] in the area are totally inadequate, basically now serve for dog piss and shit and the few remaining trees will be dead within a year or two. Parks dept. lacks funds to address this, and guess why: 421-a no real estate tax paid. if this is City Planning at its best, one dreads not contemplate the future under its “plans”. my guess is that no one in City Planning or the top city administration or State Legislature live in the creature they are creating or allowing to emerge.