Park Avenue is about to get its first new office tower in decades as the 1957 office tower at 425 Park Avenue (catty corner to Rafael Viñoly’s 1,396-foot-tall 432 Park Avenue), once the pinnacle of modernity, is being reinvented for the 21st century via a partial demolition and a dramatic, 893-foot-tall restructuring by developer L&L Holdings and architects at Foster + Partners. The 27,950-square-foot site between East 55th and East 56th streets once supported a 30-story, 388-foot-high, 585,000-square-foot office building erected between 1954 and 1957. It was designed by the partnership of Kahn & Jacobs, who produced 61 buildings in New York during their 27-year tenure. At the time, the building’s clean vertical lines were among the first of their kind on Park Avenue, predating the landmark Seagram Building by a year.

In 1831, the New York and Harlem Railroad was laid out along Park Avenue, known as Fourth Avenue at the time. The double tracks passed next to mostly open, rural land. In 1839, a cow was struck by a train at the intersection of East 58th Street. The new railroad spurred rapid development along its run, particularly after Cornelius Vanderbilt took control in the 1860s and built the Grand Central Depot at 42nd Street in 1871. Since the 80 daily trains polluted the air and created hazardous street conditions in the now-busy part of the city, the authorities forced the magnate to build a two-mile-long tunnel between the depot and East 97th Street. The tunnel was completed in 1875, and the new green median prompted the street’s renaming to Park Avenue in 1888. At this time, the neighborhood was densely built out. An 1885 map shows the future site of the skyscraper occupied by a dozen three-story rowhomes, seven of which faced Park Avenue.

425 Park Avenue in 1885. Source: The New York Public Library via newyorkbefore.com

Once the noisy and dangerous at-grade train tracks were replaced with a green boulevard, the avenue became a hotbed of new construction. One after another, rowhomes made way for a brick canyon of luxury residences that rose to a uniform height of around 16 stories. In 1926, the plateau was broken by the 42-story peak of the Ritz Tower. Standing at 57th and Park, one block north of the future site of 425 Park, the telescoping tower excluded kitchens from individual apartments, which allowed the developer to bypass residential height limits of its time. It became the tallest apartment building in the world, a harbinger of a high-rise luxury lifestyle that would remain more popular than ever a century later.

Ritz Tower, looking north from Park Avenue and East 55th Street. The townhouses at the future site of 425 Park are on the right. 1926. Source: New York Public Library

Across the street, at 56th and Park, the 21-story, 495-room Drake Hotel lured upscale clients with innovations such as “automatic refrigeration.” Erstwhile, the block between East 55th and East 56th streets remained seemingly frozen in the 19th century. By the time the Great Depression brought the building boom to a sudden halt, the rowhome block was among the least developed along Park Avenue’s Midtown run.

The townhouses at the Park Avenue block between East 55th and East 56th streets, center. Looking southeast from East 57th Street. 1936. Photo by P.L. Sperr. Source: New York Public Library

After World War II, developers began to see Park Avenue below 59th Street as a destination for high end office space rather than luxury residences. The 1952 Lever House, together with the Seagram Building, are frequently praised for single-handedly bringing modern office buildings to Park Avenue and Midtown as a whole. However, as influential as both of these buildings were, true credit for starting the trend goes to the lesser-known but highly productive architect duo of Kahn & Jacobs.

Born in New York in 1884, Ely Jacques Kahn was one of the most prolific architects in the nation’s history. Ayn Rand, who, in 1937, spent a year as his assistant while doing research for The Fountainhead, described Kahn as the “socially acceptable architect” and “modern – within careful limits.” Though she compared him to an “abler version” of Guy Francon, a complacent architect from her novel, the immense variety of Kahn’s work throughout his career spoke of a creative virtuoso that not only kept up with the times, but often helped shape the zeitgeist itself. The hundred-plus buildings he designed, or helped design, during his 88 years of life ranged from turn-of-the-century Beaux Arts to late Modernism. Though he worked on buildings across the country, most of his commissions were high-rises in his home town.

In 1917, Kahn formed a partnership with Albert Buchman after the latter’s partner, Mortimeter J. Fox, retired from their practice. Kahn and Buchman collaborated on over 40 high-rise buildings, which include landmarks such as the 1927 Hotel Sherry-Netherland. By the time Kahn headed the firm on his own in 1930, he was established as a master of the Art Deco setback form and dynamic detailing. When the Beaux Arts Ball was held in New York in 1931, Kahn was among the handful of the city’s architectural elite invited to don the image of their buildings. In the famous photo, he can be seen standing to the right of William Van Alen, dressed as the Chrysler Building. Kahn styled himself after his 1930 Squibb Building, which he considered among his finest works.

In 1940, after a decade of near-absent commissions owing to the Great Depression, Kahn formed a partnership with Robert Allan Jacobs, the son of architect Harry Allan Jacobs. Being 21 years younger than Kahn, Jacobs was a member of the next generation not only in terms of age, but also in terms of architectural sensibilities. A graduate of Amherst College and Columbia University’s School of Architecture, Jacobs had worked for the likes of Le Corbusier, a principal pioneer of the modern movement, and New York’s Wallace K. Harrison, one of the designers of the Rockefeller Center, who, after the war, became a prolific modernist architect when he partnered with Max Abramovitz and others.

Thanks to a combination of Jacobs’ modernist background, Kahn’s ongoing shift towards streamlined simplicity, and a general postwar disdain for ornament, Kahn & Jacobs single-handedly introduced International style modernism to the New York skyline. Although the overall effect of their first few commissions was paradigm-changing, it was a smooth transition rather than a jarring break from the past. Their first major commission was the 1947 Universal Pictures Building on Park Avenue between East 56th and East 57th, between the Ritz Tower to the north and the future site of 425 Park to the south. It became the city’s first post-war skyscraper, along with Carson & Ludlin and Wallace Harrison’s 75 Rockefeller Plaza. Though the vertical lines of the rectangular 75 Rock seemed to be the opposite of Universal’s squat, horizontal setbacks, both embraced the early modern spirit while looking over the shoulder at their Art Deco predecessors. 75 Rock stood as a fusion of Rockefeller Center’s Art Deco with the striped modernist box that came to represent the quintessential mid-20th century skyscraper. Universal’s horizontal window bands shared more in common with Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye in France than with its ornamented neighbors. On the other hand, the limestone bands of both structures spoke to the likes of the Empire State Building, and Universal’s “wedding cake” silhouette followed the setback tradition set in motion the 1916 Zoning Law.

Kahn & Jacobs’ sophomore effort at 100 Park Avenue, 15 blocks south of Universal, was a much bolder foray into the International style. The glass curtain wall of the 36-story, 1949 office tower, with its thin metal mullions and spandrels between windows, was unlike anything the city has seen before. Even trend-setting landmarks such as the Lever House and Seagram owe much the accomplishment at 100 Park. By the time Kahn & Jacobs’ 42-story, rectangular office stack at 1407 Broadway opened its doors in 1950, it was hard to imagine that the same architect had designed two setback Art Deco buildings across the street just 19 years earlier.

But while even the pair’s most daring efforts referenced the past in one way or another, other designers took modernism to a whole new level. Three blocks south of Universal Pictures Building, Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill built the Lever House. The 21-story, green glass rectangle sat upon a horizontal base, elevated above the ground plane via a forest of evenly spaced columns. The composition was even more decidedly modern than Oscar Niemeyer, Le Corbusier, and Wallace Harrison’s 1952 United Nations Secretariat Building, the city’s first skyscraper to use a glass curtain wall.

In the meanwhile, Kahn & Jacobs continued with their principle of looking forward while referencing the past. 425 Park Avenue was the duo’s ninth collaboration, replacing the rowhouse group across East 56th Street from the United Pictures Building. It took the basic setback form of its predecessor and moved it one step closer to quintessential International style. The stretched form resembled 100 Park rather than the classic “wedding cake” shape, rising from the sidewalk as a 12-story block, topped with 2- and 3-story setbacks that transitioned the form into a slender, 13-story tower. Though its vertical, ornament-free lines spoke of its time, its materiality straddled the past and the present. Narrow, double-hung windows spaced with dark glass spandrels made for a glassy curtain wall, but the white brick mullions in between referenced the avenue’s recent, pre-war past.

Unlike Seagram’s colonnade grid, the base of 425 Park was rather conventional, with storefront windows framed within plain stone panels. The only decoration came in the form of twin, angled flagpoles that hung above the main entrance. Prior to the ongoing reconstruction, the latest tenants of the Park Avenue-facing ground floor space were Sterling National Bank, a Duane Reade pharmacy, and Staples. On the south side, at East 55th Street, the Create & Go restaurant was sandwiched between the building’s service bay and a public garage entrance in the basement levels. The building faced the interior of the block to the east with a vertical, mostly windowless service core clad in white brick.

The building well represented the firm’s current style. Their other 1957 commission, the 38-story 1065 Avenue of the Americas , was if not an identical, then at least a fraternal twin to 425 Park. Since its smaller lot had twice as little avenue frontage, it appeared as if 425 Park was split in half down the middle. 1065 was even more game-changing for Sixth Avenue than 425 was for Park, as it was the first International style high-rise on what soon became one of the city’s most powerful skyscraper canyons, where modernist boxes march for a nearly unbroken, 20-block stretch.

After working on 30 plain brick buildings for the Douglass and Carver housing projects, the duo joined Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson as associate architects for one of the defining buildings of its generation, the Seagram Building at 375 Park Avenue. Completed one year after 425 Park, and two blocks to the south, the 38-story Seagram was a minimalist crescendo in the decades-long symphony where modernist maestros stripped down ornamented office obelisks to pure, minimal forms. In a sense, the building was a fusion of the concepts introduced by Lever House and 425 Park. Its simple, rectangular form was defined by thin mullions that contained vertical bands of narrow windows. The tower’s freshest invention was its reimagining of the 1916 Zoning Law, as it fronted the building with an open plaza rather than a series of setbacks. A commonly held notion claims that Seagram single-handedly spawned countless, and generally inferior, imitators. However, the claim is only partially correct. While Seagram did introduce the plaza-and-tower setup, the striped, steel-and-glass boxes that followed in its wake were the continuation of a gradual stylistic evolution, where Seagram was just one, albeit a very important, link in a long chain. And although the results ranged from pleasant to abysmal, very few subsequent modernist towers reached the level of finesse observed at the landmark at 375 Park Avenue.

Unfortunately, the firm of Kahn & Jacobs, which continued to produce buildings until Kahn’s death in 1972, was no exception to the rule. While their work left an undeniable imprint on the city’s storied skyline, the duo seemed to slow down their dynamic stride. They never again reached the level of innovation of their early years, sticking to the old formula more often than treading new paths. The more concerning issue was that a number of their buildings aged poorly over the years, both physically and from the aesthetic perspective. Their last work, the 41-story 1095 Avenue of the Americas, fronting Bryant Park’s west side, received a facelift only 32 years after its 1974 completion, where its dramatic black-and-white vertical stripes were swapped for a lighter-feeling, environmentally and literally green, glass curtain wall. For all its innovation, 100 Park Avenue did not stand the test of time, when SL Green Realty Corp. and Prudential Real Estate Investors replaced its metal mullions with a sleek glass façade wall in 2008. Time will tell whether the redesign is seen as a move in the right direction or senseless defacement of a groundbreaking design, but at the moment, the final product looks refreshing and there was no love lost for the old look if internet comments are any indication. The 27-story New York Stock Exchange Annex at 20 Broad Street is on the drawing boards for a residential conversion, where the extent of exterior alterations is yet unknown.

The most dramatic change of all is underway at 425 Park. The Park Avenue corridor featured some of the city’s sleekest office space in postwar America, immortalized on television by Mad Men. But at the start of the new millennium, the outdated buildings were falling behind their new counterparts in other parts of the city. Park Avenue’s last new office tower was I.M. Pei’s 27-story 499 Park Avenue, erected at the corner of 59th Street in 1980. The last full-block office project on the avenue went up almost half a century ago. In order to stay competitive, the city is pushing for rezoning Midtown East for denser construction, which would make redevelopment of aging properties along Park Avenue and on the surrounding blocks a lucrative prospect.

In the meanwhile, the block was already growing hot. In the past few years, land values along 57th Street skyrocketed as high as the residential supertalls that are currently growing along the freshly dubbed Billionaires’ Row. In 2007, the pre-war Drake Hotel catty corner to 425 Park was torn down to make way for 432 Park Avenue. At 1,396 feet, it would briefly restore the city’s claim to the world’s tallest residential building, until Dubai’s Marina 101 beats it by three feet. In 2011, the Observer named 432 Park, along with 425 Park, as two of the city’s ten most valuable development sites.

Given the favorable real estate climate, developer L&L Holding chose against waiting for the city to finalize plans for the upzoning, which would extend the 15 year planning process even longer. In 2012, they announced their intent to erect Park Avenue’s first new office building in more than three decades by redeveloping 425 Park. Thanks to obscure and outdated zoning stipulations, if they chose to demolish the original building entirely, they would only be permitted to erect a smaller project. On the other hand, if they maintained 25 percent of the original structure, they would be allowed to add more floor space.

Like the developers of the 1957 building, L&L Holdings sought to attract clients via cutting-edge architecture. In a bid to create iconic office space, they reached out to eleven architecture firms. “We want to work with the best architectural minds out there, because we have some very important things to achieve and to deal with,” says David Levinson, L&L’s chief executive, as per the Wall Street Journal’s April 2012 report.

425 Park Avenue competition finalists. Top left: Zaha Hadid Architects. Top right: Office for Metropolitan Architecture. Bottom Left: Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners. Bottom right: Foster + Partners. Image via unit5bartlett.wordpress.com

The final selection was narrowed down to four submissions from Pritzker-prize winning architects: Foster + Partners, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, Office for Metropolitan Architecture, and the firm of the late and great Zaha Hadid. All four incorporated the base of the original building, topped with a skyscraper that speaks to the designer’s signature style: Foster’s clean glass stack of structurally expressed floors, Rogers’ hanging gardens between exposed steel diagrids, OMA’s twisting stack of cubes that seems to jump straight off the pages of Rem Koolhaas’ Generic City, and Hadid’s skinny-waisted, curvy skyscraper. Each of the four would have been a fine addition to the city’s legendary architectural legacy and a worthy successor to Park Avenue’s masters of modernism from the previous era.

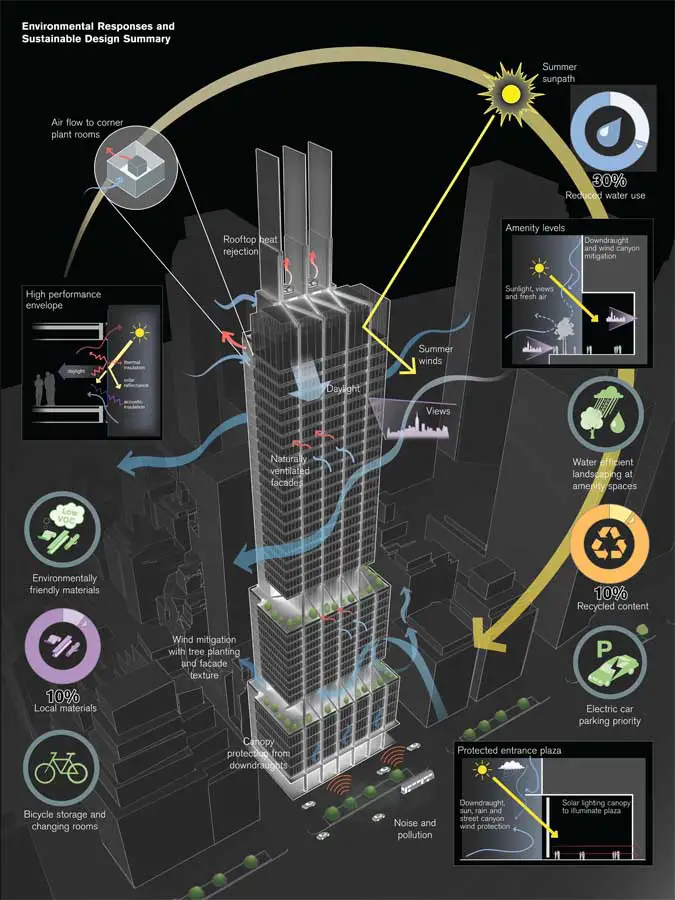

A skygarden. Image by Foster + Partners via e-architect.co.uk

In the end, the proposal by Foster + Partners carried the day. While it does not engage as many striking slopes and curves as its counterparts, the 893-foot-tall building will have the most pronounced skyline effect. Three dramatic concrete fins jut about 200 feet above the roof level and provide robust vertical thrust to the 47-story tower. Below, the glass-clad floors are massed in three rectangular sections. Though the fins have somewhat of an Art Deco flair, the curtain wall pays homage to its International Style predecessors. The horizontal window bands reference the Universal Pictures Building to the north, while vertical white mullions and a rear-set core come off as a modern reimagining of the original office building at the site. Tall ceilings and abundant sunlight characterize the interiors. The tower will be anchored by a 45-foot-tall lobby and accented with sky gardens on the setbacks. The design emphasizes its green features, which include environmentally-friendly materials, bicycle storage and changing rooms, and a high-energy performance envelope.

Image by Foster + partners via e-architect.co.uk

Demolition commenced in 2015. By July, the tower was wrapped in black netting, and exterior dismantling started making visible progress by fall. At the moment, the top half of the tower is gone, and interior demolition is in full swing.

Since the days of New Amsterdam, the city’s developers had to stay ahead of the competition to attract the most valuable clients. Large size and prime location make for the winning formula in office real estate, as evidenced by the $3.4 billion, almost two-million-square-foot General Motors Building at 767 Fifth Avenue, the city’s most expensive. However, innovative design is another factor that may push the price into the stratosphere, recouping the associated higher costs. L&L Holdings placed the same bet at 425 Park Avenue as their predecessors did in the 1950s, and the gamble seems to be paying off already. Earlier this year Citadel, one of the world’s largest hedge funds, signed the most expensive lease in the city’s, and possibly the country’s, history. Of course, when forward-looking, responsible design is in play, the winner is not only the developer’s bank account, but also every New Yorker that has to interact with the uplifting edifice.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews